I’ve made just about every dust collection mistake you can think of.

Over the years of setting up my shop, I tried to save money where I shouldn’t have, trusted airflow numbers that weren’t realistic, and built ductwork that looked great on paper but quickly turned into clogging headaches.

What I’ve learned is that dust collection isn’t about one piece of equipment—it’s about the entire system working together.

Every shop is different, but one principle always applies: airflow is king. If you remember nothing else, let it be that.

1. Relying on a Shop Vacuum for Everything

A shop vac is incredibly useful, but it’s not designed to be a complete dust collection solution. It moves air at high pressure but in relatively small volume.

That’s why it works so well when the hose is just a few inches away from a router bit, a sander, or other handheld tools. The suction feels strong because the system is optimized for close-range collection.

The problem comes when you expect that same vacuum to handle tools like a planer or table saw, which generate massive volumes of chips and dust far away from the collection port.

At that point, a shop vac simply can’t keep up—it doesn’t move enough air over distance to capture what’s produced. The fix is to use shop vacs for what they do best: small tools and short hoses.

For larger machines, even a modest single-stage collector is a big improvement and will keep your shop from filling with chips.

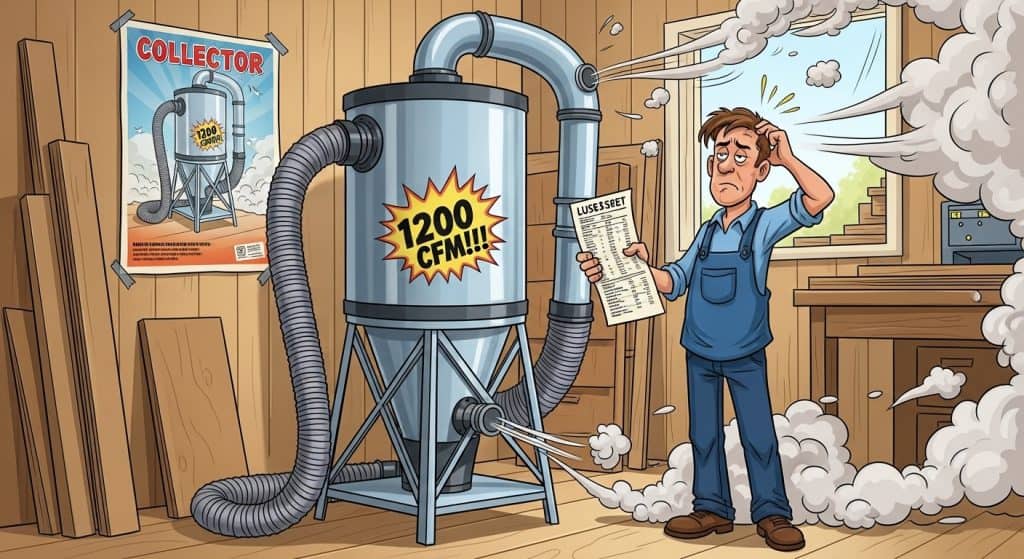

2. Taking Dust Collector Specs at Face Value

Dust collector marketing can be misleading. When you see a spec sheet listing airflow at 1,200 CFM, that number was usually measured with no ducting, no filter, and no resistance—basically the motor spinning freely in open air.

The moment you attach a bag, filter, or duct run, the airflow drops significantly, sometimes by half or more. I learned this the hard way when my collector underperformed badly compared to its advertised specs.

The solution is to understand what those numbers really mean and plan accordingly. Single-stage collectors can do a good job of picking up larger chips and dust that would otherwise pile up on the floor, but they’re not ideal for capturing fine airborne dust.

If you care about cleaner air and better filtration, look for a system with a high-quality canister filter or a true cyclone.

3. Expecting a Cyclone Add-On to Fix Everything

Cyclone add-ons are popular because they promise better separation of dust before it reaches your filter. But what they don’t do is increase airflow.

I once thought adding a cyclone attachment to my undersized single-stage collector would give it the power of a full cyclone system. In reality, it only added resistance without improving suction. The motor and impeller determine how much air moves—no add-on can change that.

If you want the true benefits of a cyclone system—longer filter life, better chip separation, and the ability to handle multiple machines—you need a unit designed for that purpose.

A proper cyclone has a larger impeller, more powerful motor, and efficient design to maintain airflow. If your current collector is weak, no bolt-on accessory will magically make it strong.

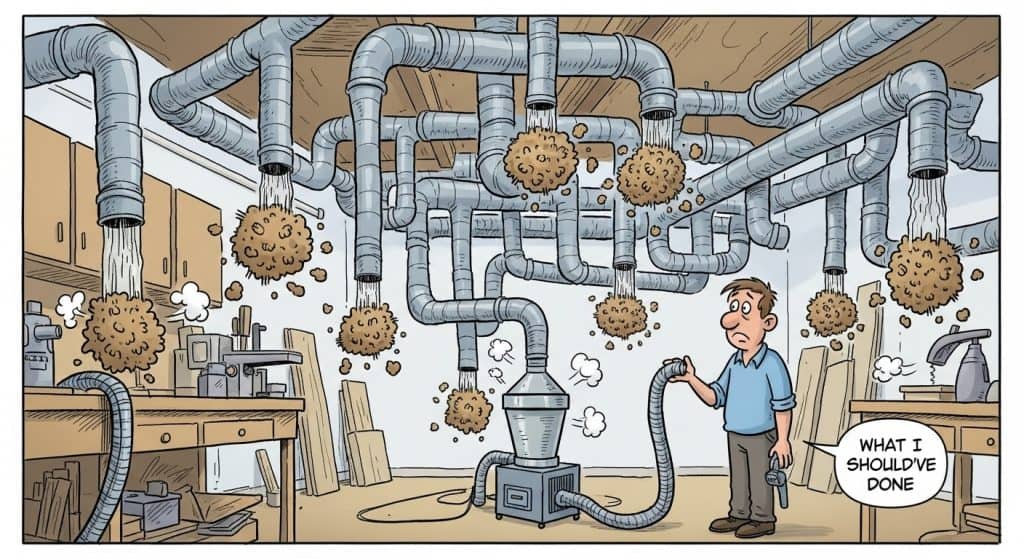

4. Over-Ducting an Underpowered System

When I first started laying out ductwork in my shop, I wanted to connect every machine with long mains and multiple branches.

The problem was that my small single-stage collector just didn’t have the airflow to handle that much resistance. Chips piled up in the lines, clogs formed constantly, and the suction at the tools was barely noticeable.

The lesson I learned is that ductwork design has to match the power of the collector. With a shop vac or small single-stage collector, keep the runs as short and direct as possible—just a hose to the tool and back.

If you want a central ducting system that serves multiple machines, you need to step up to a cyclone with enough capacity. Otherwise, you’re just choking your system and creating more frustration.

5. Choosing the Wrong Duct Material or Size

Duct choice matters more than many people realize. I once tried to save money by using standard HVAC pipe, but the seams faced the wrong direction and snagged chips constantly.

Leaks appeared almost immediately, and performance was disappointing. Smooth-walled duct, whether PVC or steel designed for dust collection, makes a huge difference by reducing friction and keeping airflow steady.

Sizing is just as critical. A 4″ duct is usually the sweet spot for single-stage collectors, while larger cyclones are built for 6″ mains or bigger.

If you undersize your duct, you restrict airflow and overwork the blower. Oversize it and airspeed drops so dust falls out in the line instead of reaching the collector.

The solution is to match your duct size to your system and avoid shortcuts with materials not meant for dust collection.

6. Overusing Fittings, Bends, and Flex Hose

Airflow behaves like a moving mass with momentum—it doesn’t like sharp turns or rough surfaces.

Early on, I used too many tight 90° elbows and long stretches of flex hose, and my collector’s performance dropped dramatically. Every bend and every ridge adds turbulence, which slows airflow and allows dust to settle.

The fix is to design duct runs with as few fittings as possible. When you do need to turn, use gradual bends instead of sharp elbows. Two 45° fittings with a short straight section in between create far less resistance than a single 90°.

Limit flex hose to the shortest possible length—just enough to connect to a machine where you need movement. The smoother and straighter the path, the better your system will perform.

7. Misplacing or Ignoring Blast Gates

Blast gates are a simple way to control airflow, but they can cause problems if used incorrectly.

I’ve had gates installed backwards that leaked constantly, and I’ve had others clog up with dust in the slots so they wouldn’t fully close.

It’s easy to overlook them, but their placement and orientation matter more than you’d think.

A better approach is to install blast gates close to the main duct rather than right at every machine. This reduces the number of fittings between the collector and the gate, which minimizes leakage and keeps suction strong where you need it.

It also makes the system easier to manage by letting you shut off entire branches when they’re not in use.

8. Overlooking Fire and Filter Risks

Vacuuming the shop floor into a dust collector seems convenient, but it can be dangerous. Metal screws, nails, or even small shavings can get sucked into the impeller and create sparks.

Those sparks can sit smoldering in a dust bag for hours before igniting.

The solution is to be proactive. Sweep up visible debris first, use magnets near floor sweeps to catch stray metal, or install a separator to trap large pieces before they reach the collector.

Filters also require care—don’t assume you can just swap in a finer bag like a furnace filter. Fine dust needs far more surface area to filter properly, which is why pleated canister filters are the best upgrade.

They allow better airflow while capturing finer particles, keeping your air cleaner without strangling your system.

9. Blindly Adding Separators

Separators are great at keeping chips out of your filter, but they’re not without trade-offs.

I once added a trash-can separator to a small collector and immediately noticed weaker suction at the tools. That’s because separators add resistance, which reduces the overall airflow reaching your machines.

If your system is already underpowered, a separator may do more harm than good. The right way to use one is to pair it with a collector that has enough capacity to handle the added resistance.

Keep duct runs short, minimize bends, and accept that separators extend filter life at the cost of airflow. They’re useful, but they’re not a magic upgrade.

Bonus Tip: Dust Collection When Sanding

Sanding creates some of the finest and most dangerous dust in the shop. It lingers in the air long after you’re done working, and a weak collection setup won’t catch much of it.

In a perfect world, you’d have a dedicated dust extractor specifically designed for sanding. These machines move less air than a full collector but at very high suction, which is exactly what sanding requires.

I own a Festool dust extractor, and it’s one of the best upgrades I’ve ever made. It’s quiet, powerful, and built for the task of capturing sanding dust at the source. That said, dust extractors can be expensive, and not everyone wants to invest in one right away.

- HEPA Certified: HEPA filtration, adjustable high performance turbine. Capture dust without…

- Cleaning Tools Included: For the CT 15, the crevice and upholstery nozzle cleaning accessories are…

- High quality: Robust design for a long service life, compact and stable footprint and a chassis with…

A good alternative is to pair your sander with a shop vac fitted with a HEPA filter and a quality hose. It won’t be as refined as a true extractor, but it will capture most of the dust and keep the air much cleaner than sanding without one.

Quick Suggested Setups

Small Shop

For a small shop, a good setup is a shop vacuum with a short hose for handheld tools, plus a simple single-stage collector dedicated to one stationary machine at a time.

This keeps dust under control without overcomplicating things.

Medium Shop

For a medium shop, step up to a single-stage collector with 4″ ductwork, a canister filter upgrade, and short runs of smooth pipe.

Use blast gates to manage airflow between two or three machines, and avoid long flex hose runs.

Large Shop

For a large shop, a cyclone system with 6″ mains, proper steel ductwork, and pleated filters is the most effective choice.

It provides the airflow needed for multiple machines, cleaner filters, and much better fine dust control for the whole shop.

Last update on 2025-11-01 / Affiliate links / Images from Amazon Product Advertising API